Bell ringer, acrobat, apothecary, grocer, grocer, hardware and nail makers, quilter, blacksmith, cooper, coachman, stenodactylographer... All these trades occupied generations of workers before being relegated to the history books by industrialization. Today, the debates around technological unemployment are once again at the heart of the news with the advent of the fourth industrial revolution, embodied by artificial intelligence and connected machines.[1]. Are we therefore at the dawn of the end of work as we knew it and thought of it in the discourses, the collective imagination and the current functioning of society, that is to say the employment of employees and small self-employed persons[2] ? Anti-tech analysis makes it possible to contextualize the frenzied race for AI in a longer history of the alienation of people from the techno-industrial system, where workers are reduced to replaceable appendages of ever more efficient and autonomous machines.

The very concrete impact of the development of AI

Artificial intelligence is a computing superpower that makes it possible to automate repetitive tasks or, through the extremely rapid analysis of an insane amount of data and information, to generate texts, images or sounds. This is why we can rightly fear layoffs in favor of machines that are more efficient and less fallible than human beings, the latter being exposed to injuries, accidents, burn-outs, etc.

A deep sense of concern has thus been sweeping through society for several years now. She sometimes makes appearances in the news, such as during the strike of Hollywood writers who feared being replaced by AIs.

The fact is that every industrial revolution has been accompanied by a change in the world of work.[3]. Businesses, multinationals and governments have always sought to exploit new techniques and technologies to increase productivity, and those that did not have disappeared. During the 19th centuryE and XXE centuries, almost all agricultural and craft jobs disappeared in favor of the secondary sector with massive industrialization and rural exodus. Starting in the 1970s, we are witnessing the tertiarization of work, that is to say, the explosion of service professions and no longer of production, in particular due to the opening up of global trade and relocations. Deindustrialization, which has caused so much turmoil and social struggles, has nothing to do with political interference; 65% of this societal upheaval is due to technical progress, according to a report by the General Inspectorate of Finances[4]. However, at the dawn of a new industrial revolution with AI, one might wonder what will happen to the overwhelming majority of people working in the tertiary sector if machines can perform their tasks.

In fact, it is accepted that our so-called “advanced” economies have been losing productivity growth since 2008. It is even envisaged that the growth in the labour supply could fall to zero between 2030 and 2040. Technocrats therefore believe that productivity fuelled by technology would be welcome.[5], and expect AI to fill a growth gap with a new leap forward. This manoeuvre has already dramatic ecological and social consequences.

The most important study on AI and mass unemployment was carried out just over a year ago. According to this study, based in the United States, a quarter of current professional tasks could be automated[6]. Among the most exposed sectors, we can cite among others the administrative, legal, journalism, with editorial secretaries for example, the graphic design community or even — paradoxically — that of Tech. In France, a 2018 report states that these are the positions of unskilled workers in the industries of Process, handling, building finishing, mechanics, maintenance workers and cashier workers who will be the first to be replaced by machines[7].

These studies make it possible to distinguish replacement, i.e. the total disappearance of jobs, from “complement”, where only a portion of employee tasks are automated. Such a scenario also suggests numerous problems: a decrease in salary, working time leading, for example, to the accumulation of jobs, new methods of exploiting workers by forcing them to do new tasks in a more or less informal way, etc. With the obligation to “improve skills” to keep their work induced by the imposition of new technologies, bosses will impose training and adaptations to take control of these tools. But just as with the digital penetration of the world of work, many people will be left behind, which will only exacerbate tensions and inequalities. In all, 70% of jobs could be replaced or radically changed by AI. In the United States and Europe, 300,000 million jobs are exposed to AI-powered automation[8].

AI will lead to a violent transformation of the world of work and this is logical: the aim of AI is to automate human actions. Its raison d'être is therefore the elimination of jobs. Faced with this, workers and unions are in difficulty due to the complexity of these technologies, and the ever more opaque entanglement of the actors involved in their development.

A profound change in the world of work despite the reassuring speeches of technocrats

Technocrats, as is well known, are concerned about the fate of the masses and concerned with the consequences of the penetration of the technologies they develop into society. They are thus trying to reassure workers: the replacement of employees by machines will be accompanied by the displacement of jobs, social plans and the development of AI will lead to a prosperous reindustrialization for all.

However, it is already clear that a large part of the jobs created by AI will be highly qualified engineering jobs.[9]. This will drastically reinforce educational inequalities to the detriment of people less comfortable with mathematics, or simply those who cannot adapt to the ultra-coercive and normalising framework of the school system.

Let's not forget, moreover, that we are all already put to work by AI companies: we feed our data and more or less creative content into social networks for free, we produce information flows on our smartphones that feed and improve AI software. There is also what the sociologist Antonio Casilli calls the Digital Labor : precarious microworkers and chatbot testers who “propel the virality of brands, filter pornographic and violent images, or enter text fragments in a row to operate machine translation software”[10].”

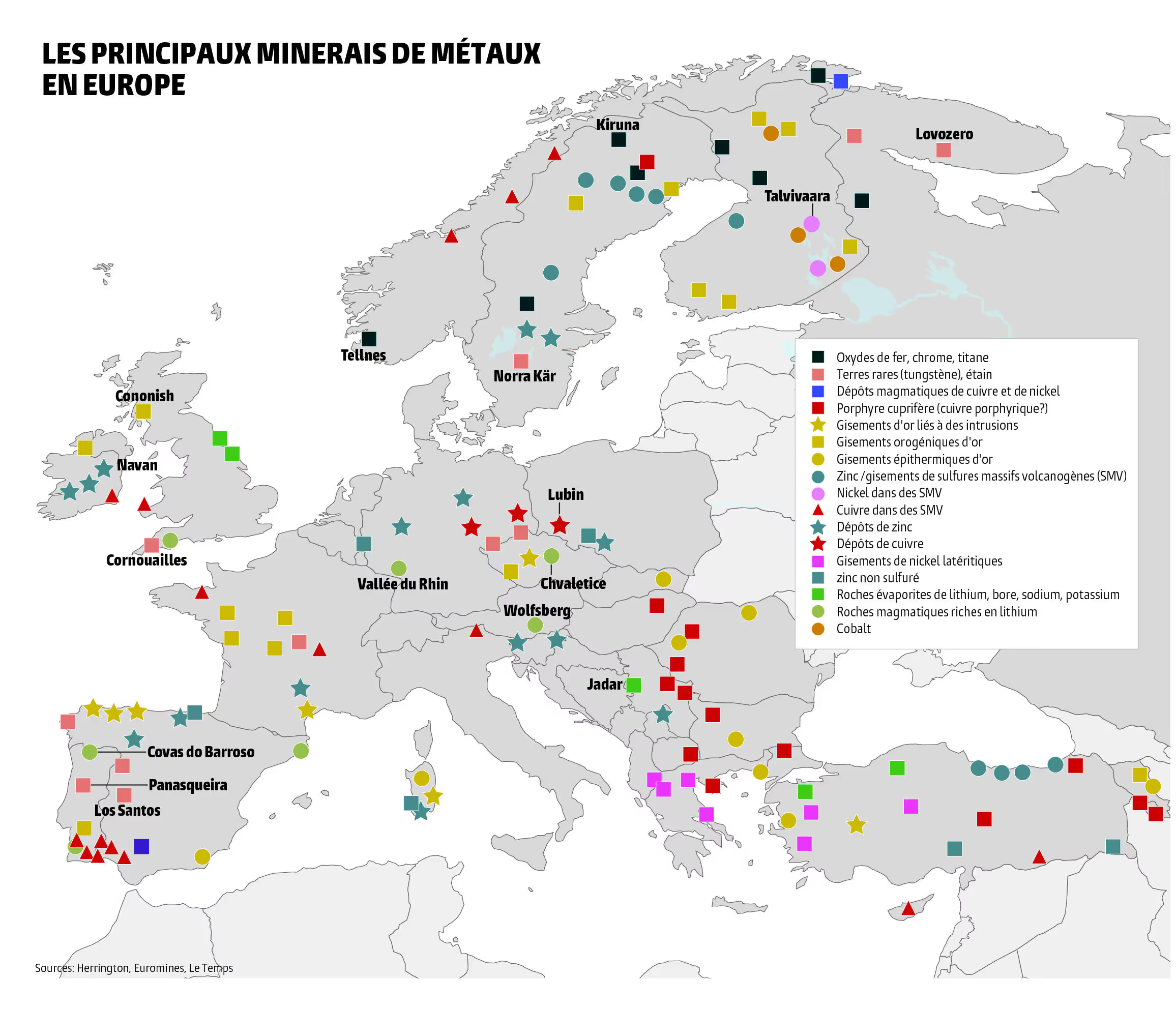

We could also think that artificial intelligence will lead to a prodigal reindustrialization of high school jobs. Indeed, while GAFAM and the media maintain, through various dishonest processes, the illusion of a minimal environmental footprint of digital technology and AI, going so far as to speak of dematerialization.[11], it is crucial to remember that to make AI systems work, rare metal mines, factories to process and transform these raw materials, and data storage and transport infrastructures are needed. These sectors require labour, but we must not forget that most mines are operated in other countries, where safety regulations and the Labor Code are more flexible and make it possible to force people to handle ultra-toxic substances and to devastate ecosystems without accountability. They are therefore precarious jobs carried out in conditions harmful to workers and the environment. In so-called “favoured” countries, each new project gives rise to strong and legitimate disputes because of the destruction they cause. AI software, which consumes phenomenal amounts of water and energy, will lead to water and electricity rationing that will increase tensions even more. Is it desirable for workers to depend on an ultra-polluting sector, which will make ecological and social struggles ever more difficult to reconcile?

In addition, let's not forget that AI already has extremely negative concrete impacts on the world of work: in hiring, already, where we can recall the scandal of these AI software that rejects applications on the basis of origin, gender, age or disability, since AI accentuates discrimination and exceeds regulations on equality at work.[12].

Let's also mention these algorithmic surveillance software that makes it possible to observe and analyze employees: the control of bosses, in the same way as that of the police and the State in the streets, is being strengthened exponentially with artificial intelligence[13].

We come to the dystopian model of Data Driven Manufacture, factories in which

“sensors are placed throughout the industrial chain, from design units to production and logistics units, generating masses of data processed by machines capable of interpreting a large number of situations in real time and of immediately dictating to certain categories of personnel the actions to be taken. [...] These techniques were in particular experimented with in Amazon warehouses in which material handlers receive instructions from audio headsets from computer systems indicating to them. [...] These techniques were in particular experimented with in Amazon warehouses in which handlers receive instructions from audio headsets from computer systems telling them Indefinitely which product will be collected in this department, before depositing it mechanically in such a container[14].”

This kind of technology depoliticizes work and further hampers social protest by making the stranglehold of employers and technocrats over workers invisible.

Nor should we be fooled by the earthly paradise that some techno-utopians sell: the automation of work by AI will not free humans from earthly necessities to give free rein to everyone's creativity and generalize idleness: even if some manage to free up time thanks to automation, it will certainly be exploited by the leisure industry.[15]. In addition, anthropology teaches us that material comfort is progressing always thanks to the increase in inequalities.

These few examples clearly show that no stratum of society will be spared by the deployment of AI software. Beyond a more or less fantasized end of work and mass technological unemployment, it is indeed a profound transformation of the world of work that will result from this new industrial revolution, where human beings will be ever more alienated, superfluous, and controlled; at the mercy of the technocrats who develop these technologies.

AI, a new stage in the realization of the fantasy of technoscientific deliverance

It is essential to always remember that artificial intelligence research is not neutral; it is indeed a quest for power and power on the part of the institutions and entities that fund it. Artificial intelligence therefore inherits two ideologies: the desire to control the populations of modern nation states, and the technological fetishism of technocratic industrialists. Thus, while the exploits of some AI software may seem frightening and aroused fearful admiration, it should be remembered that these technologies are part of a historical process that has been going on for a long time, and in which they represent only one stage. The aim: to do without workers entirely, by delegating all production to perfect machines, in order to free industrial capitalism from social protest.

In 1824, Henri de Saint-Simon founds an industrialist “religion”, based on the belief in perfect and virtuous management of society and the living world through technology. After the Second World War, traumatized by the atrocities he witnessed (and in which he actively participated by working for the American air force and army), Norbert Wiener developed the cybernetic movement. Emerging in the fifties, its aim is to “provide a unified vision of the emerging fields of automation, electronics and mathematical information theory, as an “entire theory of command and communication, both in animals and in machines.” Cybernetics

“gives rise to the idea that computing machines could go beyond their classical and legitimate functions of classifying, indexing, and easily manipulating quantitative information for that illegitimate one as a substitute for qualitative human decisions. This idea has been the current breeding ground for overfunded artificial intelligence research since the beginning of the 2000s [...][16] ”. AI research therefore appears here, not as a breakthrough, but as part of the continuity of a long history. In its links with industrialism and cybernetics, AI gives rise to “injunctive algorithmic management, seeking maximum efficiency in its conceptual configuration.[17].”

This brief historical parenthesis makes it possible to strongly question the myth of technoscientific deliverance as defined by Aurélien Berlan.[18] ; the history of proletarianization and the destruction of the environment can no longer be definitively separated from that of technical progress and industrialization. If, once again, we are being reinforced with AI the fallacious argument for the delivery of painful and repetitive tasks by machines, with the promise of a “diversification” of jobs, as if AI were going to make jobs more interesting, it is crucial not to be fooled by these speeches. The ultimate objective of AI, despite all the social plans and regulations that may be granted by states and bosses, is to make humans superfluous, a characteristic identified by Hannah Arendt as inherent in totalitarian systems.[19].

Each industrial revolution, each wave of technical innovations has given rise to criticisms, disputes and revolts.[20]. AI, despite the reassuring speeches of technocrats, must also be rejected, for all the reasons mentioned so far, which are not exhaustive. As Sebastian Cortès reminds us: “Computing is a dreadful trap that confers an apparent freedom to better lock us in. The authoritarian and hierarchical, pyramidal and patronizing form of industrial capitalism has evolved, but is still there, under a veneer. cool, young, modern. Taylorism and Fordism have not disappeared, but have taken on new forms: information technology, embodied in the computer, is their new physical medium, digital technology their new technology, Internet their new network, but work is still their first concrete application.[21] ” Questioning the impact of artificial intelligence is tantamount to criticizing the impact of technical progress on work and industrial capitalism in its entirety:

“So it is a question of criticizing, at the same time as digital technology, the society that goes with it, and the whole of society, because it is now entirely under the influence of this technology — and vice versa. Digital technology and neoliberalism go hand in hand: would there have been massive relocations of factories if there had not been the computerization of stock exchange exchanges? Unemployment benefits that are more and more difficult to access and minimum wage for all without employer contributions go hand in hand with the immense popularization of the status of auto-entrepreneur and the rampant atomization of everyone behind their screen. Exactly the same capitalist logic is at work. Digital technology does not stand alone. Fewer collective rights and more apparent individual possibilities: each for himself, and all in the wall[22] ! ”

The deployment of AI in the world of work and the legitimate concerns it generates are an opportunity to recall the dangers inherent in industrial capitalism, the impasse represented by regulation and reformism, and the need for an anti-tech revolution in order to cut the grass under the foot of new and ever more totalitarian and environmentally unsustainable forms of exploitation.