“Technological innovations are similar to laws or public institutions setting a framework that will last several generations.”

— Langdon Winner

Technology neutrality is one of the great illusions of the modern age, and perhaps one of its founding myths. However, it is not necessary to think about it very long to notice the trick. At a time when QR Code and smartphone are rapidly changing the entire society towards the industrial farming model, this idea of neutrality should be widely questioned. That is what we are trying to do here. Through several examples and reflections of technocritical authors, we will see that technical progress has led to the emergence of an authoritarian form of government through the establishment, continuously and without any democratic consultation, of dependencies and/or new material constraints. Technological choices are eminently choices policies[1].

The reign of “technical macrosystems”

Let's start with the railway, a technology considered beneficial in the collective imagination, especially in current environmental thinking. The rise of technical macrosystems such as the railway impose new constraints and material dependencies on human populations; the speed of movement allowed by the rail network considerably reduces distances, with the result of disrupting the economy and the social fabric. But in fact, what is a technical macrosystem (MST)? It was the sociologist Alain Gras who popularized the term in France, using the concept of “large technical system” from the technology historian Thomas Parke Hughes.[2]. STDs form the basis of the technical infrastructure of modern society.

“In this technical infrastructure, a set of systems — technical macrosystems — plays a decisive role. We will describe them in detail but for now let's just define them roughly as sets composed of technical objects linked by exchange networks. Macrosystems therefore combine:

— an industrial object, in the broad sense, such as an electro-nuclear power plant;

— an organization of the distribution of flows, to continue the same example, the electrical network;

— a commercial management company to connect supply and demand, EDF in the French case.

We will see that they are thus establishing a territory of their own and feeding a kind of obsession with power, regardless of the conditions of time and space. We will find its imaginary origin at the dawn of modern times, when the emergence of the scientific vision of the world and the capitalist spirit will upset the relationships between man and nature. The expansion of big technology and the globalization of the economy, the global organization of trade and the struggle for the possession of energy sources are trends that are all part of technical macrosystems. It is therefore easy to understand not only their geopolitical importance but also their ideological value. In fact, they embody progress when it extends the Cartesian dream of making man the master and owner of nature.[3].”

According to Alain Gras, “the modern world is thus based on a technical infrastructure that is radically new in the history of mankind.” The technical macro-system marks a clear break with our technical past, which makes it possible to understand why, in the 19th century, society's resistance to “railway barbarism” was numerous.

Historian François Jarrige notes that “railways more than any other device symbolize the advent of “technical macrosystems.” They are “symbols of power and modernity”, and “their development provokes numerous debates and reactions.” He cites several 19th century criticisms and specifies that “railways evoke multiple offensive words at the beginning.” The “discomfiture” of individuals who invest in railways. and the “fear of losing control” appear among the “two main questions [...] raised at the time about trains.” That second intuition was the right one. For its normal functioning, this technology requires an upheaval of the material conditions of existence, and therefore a complete reorganization of society:

“These criticisms of the train are closely linked to the changes in temporal and spatial references introduced by the new technical system. The train changes the space experienced by replacing long-planned trips with the trivialization of the distant. In a few decades, the daily perimeter expanded from the canton to Europe. In 1840, twelve hours of gallop from Paris led to Reims, Alençon or Amiens. In 1890, in twelve hours, the steam now carried to Amsterdam or Cologne. Moreover, the requirements of the railway technical system encourage the invention of a different relationship with time. To maintain continuous traffic on an increasingly overloaded network, while avoiding accidents, fixed schedules and a time scale based on the minute must be imposed. Where the rhythms of rural life remained faithful to a cosmic time ordered by the perceptible duration of day and night, the railway contributes to imposing a different relationship to time, artificialized and mediated by mechanical counting techniques (the watch) that spread at the same time.” Faced with the emergence of the figure of the “man in a hurry”, some people nevertheless ask themselves: “Where do we run so quickly? Why the rush to arrive? Isn't it time to stop for a bit on this rapid slope where we're sliding?” The train also transforms the way we look at landscapes and, more generally, the relationship with space: “By facilitating geographic mobility, the rail draws a new, smoother and more familiar profile in the country, which has long been an aggregation of islands that are unknown to each other.” During the 19th century, the heterogeneity and immensity that prevailed under the Ancien Régime was followed by the feeling of a unified French territory under Parisian supremacy.”

He also notes that “rail undeniably stimulates economic transformations”. More precisely, the latter “accentuates the process of regional specialization and accompanies the development of intensive monoculture.[4].”

Technology philosopher and political theorist Langdon Winner joins François Jarrige on the social implications of railways. In the following passage, he quotes economic historian Alfred D. Chandler:

“Alfred D. Chandler, in his monumental study of the modern enterprise, The visible hand of managers, presents impressive documentation in favor of the hypothesis that the construction and daily functioning of numerous production, transport and communication systems, in the 19th and 20th centuries, required the development of particular social forms: a centralized, large-scale, hierarchical organization, administered by highly qualified leaders. His analysis of railway development illustrates this well: “Technology made rapid transport possible in any weather; but a safe, regular, reliable movement of goods and people, as well as the maintenance and repair of locomotives, rolling stock, as well as tracks, medians, medians, stations, rotundas and other equipment, required the creation of a well-sized administrative organization. This meant employing a set of senior managers who oversee these functional activities across a broad geographic area and assigning teams of middle and senior managers to monitor, assess, and coordinate the work of the employees responsible for day-to-day operations.” Throughout his book, Chandler shows how the technologies used in the production and distribution of electricity, chemicals, and a wide variety of industrial goods “required” or “required” this form of human association. “Thus, the operational requirements of the railroad required the creation of the first administrative hierarchies of the American economy.[5].””

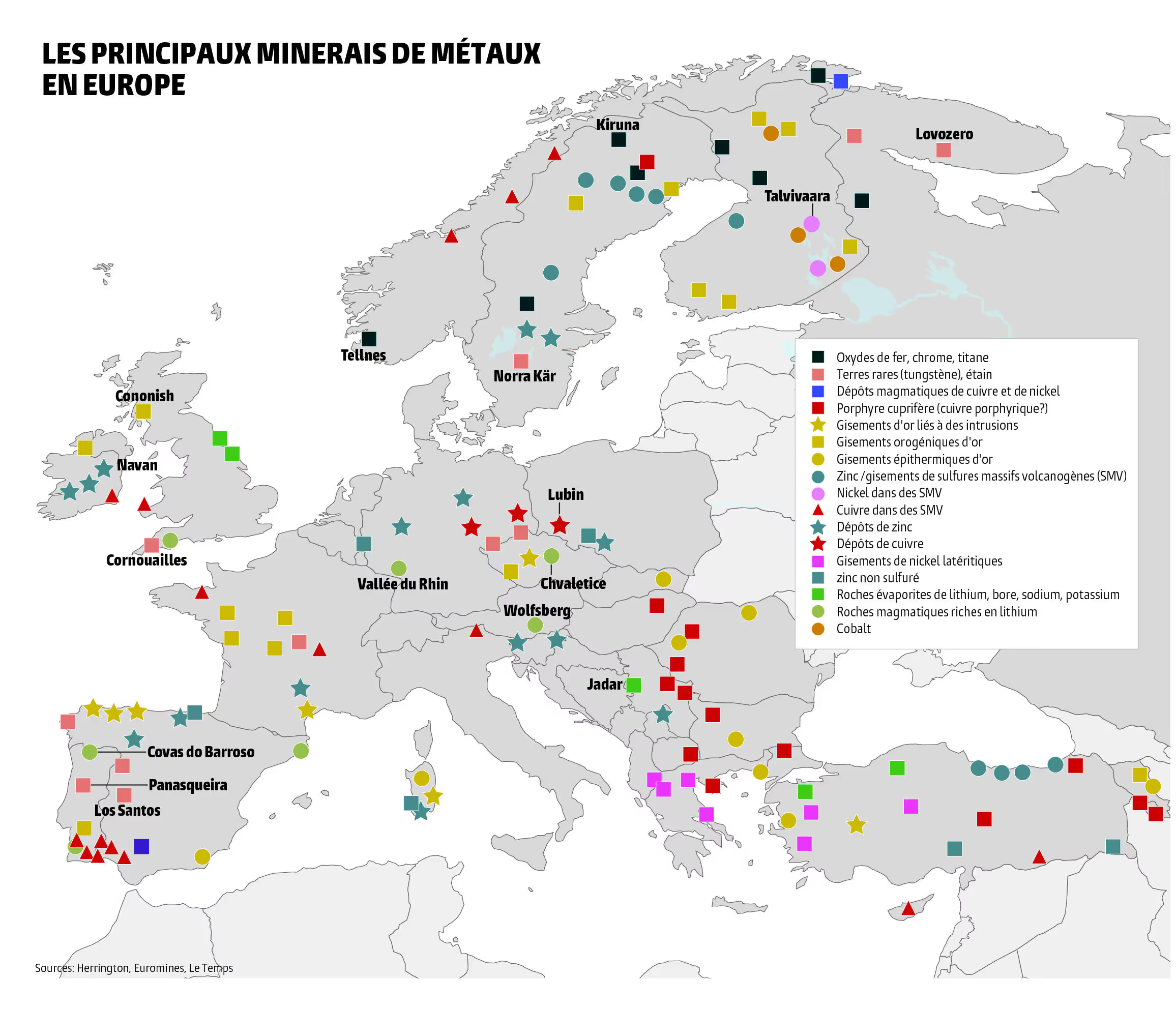

What applies to railways applies to everyday objects associated with modern comforts. Broadly speaking, the production of these objects requires extracting raw materials from various locations around the world, transporting these materials to a processing site, then transporting the intermediate product to the assembly site, and then transporting the finished product to the final consumer. Combining all the elements of such a vast and complex production chain has been made possible by the emergence of huge centralized and extremely hierarchical organizations. This is what the writer Jaime Semprun points out by using the car as an illustration:

“And so the automobile, a machine that could not be more trivial and almost archaic, which everyone agrees to find very useful and even indispensable to our freedom of movement, becomes quite another thing if we place it in the society of machines, in the general organization of which it is a simple element, a cog. We then see a whole complex system, a gigantic organism composed of roads and highways, oil fields and pipelines, gas stations and motels, organized bus trips and supermarkets with their car parks, interchanges and ring roads, interchanges and ring roads, assembly lines and “research and development” offices; but also police surveillance, signaling, codes, regulations, regulations, bypasses, bypasses, roads, roads, assembly lines, assembly lines and “research and development” offices; but also police surveillance, signaling, codes, regulations, regulations, standards, surgical care specialized, “pollution control”, mountains of used tires, batteries to be recycled, sheets to compress. And in all this, like parasites living in symbiosis with the host organism, affectionate aphids that tickle machines, men busy caring for them, maintaining them, feeding them, and still serving them when they think they are circulating on their own initiative, since they must be thus worn out and destroyed at the prescribed rate so that their reproduction, the functioning of the general system of machines, is not interrupted for a moment.[6].”

For his part, the mathematician Theodore Kaczynski gave the example of the refrigerator to show that each modern object, taken in isolation, actually depends on a gigantic technological infrastructure:

“Let's take the refrigerator as an example. Without machined parts or modern tools, it would be nearly impossible for a few local artisans to make one. If by some miracle they succeeded, it would be useless in the absence of a reliable source of electricity. It would therefore be necessary for them to build a dam on a watercourse as well as a generator. But a generator requires large quantities of copper wires. Do you think it is possible to produce these cables without modern machines? And where would they get the refrigerant gas? It would be much easier to build a cold room to store food, to dry it or brine it, as was done before the invention of the refrigerator[7].”

The same goes for the 99 electrical objects that equip the average French household.[8]. The refrigerator, the washing machine, the stove and the microwave may release some constraints, but they impose new ones, much more rigid ones. The multiplication of electrical objects is increasingly subjecting human existence to the constraints imposed by the normal functioning of the electrical system. One of these is the physical need to balance electricity production and consumption in order to avoid blackouts. Thus, a world separates a simple hammer, saw or knife made by hand from motorized tools such as an electric drill, brush cutter or chainsaw. The less we do ourselves, the more work we delegate to the machine and to the techno-industrial system to produce what we need, and the more autonomy we lose. However, material autonomy is the first condition for freedom; it is also an observable characteristic in all ecologically sustainable peasant societies.[9]. The false association between ecological society and the regression of freedoms is one of the many” Tricks ” of the technological system to ensure its reproduction.

Langdon Winner gives yet another example with energy production. He is interested in the following transition to nuclear power and the extraordinary social conditioning that this industry requires for its viability:

“The problem of the dangers of nuclear energy provides us with a particularly obvious example of the influence of the operational requirements of a technical system on public life. To compensate for the exhaustion of uranium resources, it is proposed to use plutonium, a residue of nuclear combustion in power plants, as fuel. Classic objections to this recycling of plutonium relate to its economically unacceptable cost, ecological risks and the danger of the proliferation of nuclear weapons. But behind these concerns lies a danger that is less highlighted: the sacrifice of public liberties. Expanding the use of plutonium as fuel increases the likelihood that this dangerous substance will be stolen by terrorists, mafias, or anyone else. As a result, there is a significant need for exceptional measures in order to protect plutonium against theft and to recover it in case of theft. Nuclear industry workers, but also ordinary citizens, may well be subject to security checks, discreet surveillance, eavesdropping, eavesdropping, the infiltration of informers, and even emergency measures under martial law — all of these measures being justified by the necessary protection of plutonium.

Russell W. Ayres concludes his study on the legal ramifications of plutonium reprocessing as follows: “Over time, the increase in the quantity of plutonium in circulation will put increasing pressure on the executive branch to remove the traditional controls and controls that courts and legislators impose on the executive branch and for the development of a strong central authority that is better able to provide greater security.” He says that “if plutonium is stolen, then nothing can stop the whole country from being turned upside down to get it back.” Ayres' forecasts and fears stem from the inherently political nature of technology. It remains true that, in a world where humans make and maintain artificial systems, nothing is “required” in absolute terms. However, as soon as a project is in progress, as soon as artifacts such as nuclear power plants are built and put into operation, the arguments justifying the adaptation of society to technical requirements blossom as spontaneously as daisies in the spring. “As soon as recycling has begun and the risks of plutonium theft have gone from virtual to real, nothing will be able to prevent the government from violating public liberties,” writes Ayres. From a certain point on, those who do not accept the strengthening of social requirements and constraints will become sweet dreamers and crazy people.”

Broadly speaking, it can be noted that the degree of authoritarianism tends to increase with technical progress. The more powerful a technology becomes, the more dangerous it becomes, and the more constraints it imposes on society for its viability. It is society that must adapt to technology and not the other way around. Since the machine operates according to mathematical laws, it obviously does not have the same degree of flexibility as society. It is therefore very often the former that imposes its requirements on the latter. Let's take the example of the car. The automobile made it possible to reduce distances by accelerating the individual speed of movement. But the speed of a car requires the construction of infrastructures dedicated to this particular type of machine. Because of its power, the car cannot coexist with previous means of locomotion (bipedalism, horse). Within the road system, it is therefore necessary to create a set of specific rules to optimize traffic flows and to ensure that motorists and pedestrians respect these new rules. The multiplication of cars has thus generated innumerable new constraints and material dependencies. Society has been transformed as a result.

The emergence of a “sociotechnical constitution”

“The more the device that allows us to escape natural necessity develops, the more it forces us into artificial necessities.[10] ”

— Jacques Ellul

Finally, let's take a step up with Langdon Winner to try to understand why the technological world-system tends to make human governance of human affairs obsolete. He observes that machines, factories and infrastructure networks respond, through their material requirements, to political questions that philosophers have been thinking about since ancient times. So-called “developed”, “civilized” or “industrialized” humans are increasingly dominated by the things they produce, an evolution already noticed in the 19th century by Henry David Thoreau when he wrote that “men have become the tools of their tools.[11] ”.

This condition is probably more felt nowadays at a time of energy shortage, when the spectrum of rationing imposed on the people by the State hovers (rationings intended to reserve energy for vital sectors — industry, police, army — to ensure the reproduction of the system and therefore of the dominant social order). If energy is lacking, it becomes more difficult to keep society in a state of general intoxication. For all these reasons, it is illusory to hope for progress in freedom and democracy without radically questioning our material dependence on the technological system.

Let Langdon Winner conclude:

“Over time, the cornucopia of modern industrial production gave rise to some well recognizable institutional patterns. Today, we can look back at the interconnected systems of manufacturing, communication, transport, etc. that have emerged over the past two centuries, to see that they form De facto a kind of constitution. This way of arranging things and people is not, of course, the result of the application of a political plan or theory. It appeared gradually, in stages, invention after invention, invention after invention, industry after industry, engineer project after engineer project, system after system. In retrospect, however, we can observe that these developments have certain characteristics that explain why all of these are answers to old political questions — questions of citizenship, power, authority, authority, order, order, freedom, and justice. Many of these characteristics (which would certainly have interested Plato, Rousseau, Madison, Hamilton, and Jefferson) can be summarised as follows.

First, we find the ability of transport and communication technologies to facilitate the control of events from a center, or a few centers. There was an extraordinary centralization of social control, almost devoid of checks and balances, in big business, bureaucracies, and the military. This seemed to be the most practical and rational solution. Without anyone ever explicitly choosing it, submission to extremely centralized organizations gradually became the dominant social form.

Second, we note the propensity of new means and techniques to favor the most effective human organizations in terms of size. Over the past century, more and more people have found themselves living and working in technology-based institutions that previous generations would have found gigantic. Justified by significant economies of scale and, economies or not, expressing the quantity of power that falls to large organizations, this gigantism has become a familiar environment in the material and social daily life of men.

Thirdly, there is the propensity of rational arrangements in socio-technical systems to produce their own forms of hierarchical authority. Legitimized by the need felt by all to act in the way that seems most effective and productive, the functions and relationships between men are structured in settled procedures involving order and obedience throughout an elaborate chain of commands. Thus, far from being a place of democratic freedom, the workplace is openly authoritarianism. Higher up the hierarchy, of course, those responsible justify their authority and their relative freedom by their scientific and technical expertise. At a time when forms of authority based on religion and tradition began to collapse in history, the need to build and maintain technical systems provided the means to restore a social pyramid.

Fourth, we note the propensity of large centralized and hierarchical socio-technical entities to take up all the space for them by eliminating other forms of technical activity. Thus, industrial techniques supplanted handicrafts, modern agro-industrial technologies made human-scale agriculture simply impossible, high-speed transport eliminated slower means of transport. It is not only about the extinction of techniques and tools that were once useful, it is about the disappearance of forms of social existence and individual experiences that were once alive and dependent on these techniques.

Fifthly, there are a thousand and one methods that the major socio-technical organizations use to control the social and political mechanisms that are supposed to control them. Human needs, markets, and political institutions that are supposed to regulate technological systems are often manipulated by these systems themselves. Thus, for example, certain psychologically sophisticated techniques are commonly used in the field of advertising in order to modify people's desires in order to adapt them to the existing offer. Moreover, such a practice is now found in political campaigns as well as in advertisements for deodorants or Coca-Cola (with the same success).

Many other characteristics of contemporary technological systems can appropriately be considered political phenomena. And it's certainly true that the developments I'm talking about are influenced by factors other than technology. But it's important to note that as our society adopts sociotechnical systems, some of the most important questions philosophers have ever asked about human affairs are unwittingly being answered. Should power be centralized or dispersed? What is the right size for a social organization? What is an acceptable source of authority in human associations? Is the freedom of a society linked to social uniformity or to social diversity? What structures and procedures are appropriate for deliberation and decision-making? For over a century, our answers to these questions have often been instrumental, expressed in the instrumental language of efficiency and productivity, physically embodied in systems man/machine which seem to be nothing more than a means of providing goods and services.

[...]

Of course, our sociotechnical constitution also has its founding fathers: the inventors, entrepreneurs, financers, engineers and managers who shaped the material and social dimensions of new technologies. Some of them are well known — Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, J.P. Ford, J.P. Morgan, J.P. Morgan, John D. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, Alfred P. Sloan, Thomas Watson, etc. Much less well known are the names of Theodore Vail, Samuel Insull, or William Insull, or William Mullholland, who were nevertheless equally important builders of our technological structures. In a sense, the founders of technological systems are no strangers to politics; several of them fought ferocious political battles to achieve their end. William Mullholland's ruthless machinations to bring water from Owens Valley to the desert region of Los Angeles are a classic of the genre. But the qualities of political wisdom found in the founders of the American Constitution were sorely lacking in those who designed, built, and promoted these major technical systems. These founding fathers were mainly obsessed with the lure of gain, the control of organizations and the joys of innovation. They were rarely interested in the meaning of their work for the structure of society or justice.

For those who have embraced the idea of freedom through abundance, in any case, questions about the best social order do not matter. Their technological optimism was based on the belief that any creation that could emerge in the technological sphere would certainly be compatible with freedom, democracy, and social justice. This is akin to believing that any technology, regardless of size, shape, or nature, is inherently liberating. For the reasons we have just seen, this is a very strange belief.”

S.C.