"Find below an article published in Aeon magazine in December 2021[1]. The author of Disruptions: Why Things Change (2021), history professor David Potter, describes why and how societies undergo radical change. Here’s what the influential political journal Foreign Affairs says in a review of Potter's book:

"The replacement of one world-shaping political order with another has always required strategy, leadership, and ideological struggles driven by the search for legitimacy. It is less the downtrodden and dispossessed who reshape political life than activists and charismatic leaders who latch on to potent new ideas and build new coalitions. Potter’s message to the defenders of the current era’s liberal order is to redouble their efforts to make the modern liberal state a professional servant of the people."[2]

As expected, Potter praises the liberal system and seems to advocate for a 'disruption' to reinvent it, making it fairer while continuing to support the technological system. He doesn’t seem particularly concerned that industrial society and its technologies are destroying the ecosystems that provide our food, water, and air, or that this is pushing humanity toward extinction. It’s also unrealistic to think that technological society will ever become truly equal. Since the first industrial revolution, technology has only increased inequalities, and closing that gap is now almost impossible, as a recent UN report shows [3] (summarized here). We are publishing David Potter's text mainly because of its historical and strategic value, not because we agree with the author's views.

Industrial society is currently under growing strain, which will likely lead to major upheavals in the coming years or decades. Most of the conditions that typically precede radical societal shifts seem to be in place. The technological system will undoubtedly try to reorganize society to ensure its survival. If it manages to solve the energy and raw material crises, we could be on the verge of a new industrial revolution, especially with the ever-increasing power of machines, driven by advancements like artificial intelligence. This new industrial revolution is exactly what the Shift Project, led by engineer Jean-Marc Jancovici, advocates for ('Europe must lead the way to the next industrial revolution, the one beyond fossil fuels [4]').

For those who view high technology—and the industrial system as a whole—as a threat to the survival of humanity and other species, regardless of the energy source, a major upcoming challenge will be preventing this systemic transformation. Instead of reorganizing the industrial system to extend its lifespan, we must push for its complete dismantling. As mathematician Alexandre Grothendieck pointed out in the 1970s [5], there are no solutions to today’s social and ecological problems within the framework of industrial society. We need to significantly reduce the technological level of our societies. This should be the top priority for anyone who genuinely cares about the future of our planet and its inhabitants.

How disruptions happen

Major disruptions in world history follow a clear pattern. What can upheavals of the past tell us about our own future?

On 3 April 1917, a crowd gathered to meet a train arriving from Helsinki at Petrograd’s Finland Station. The train carried Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. He greeted his audience with a speech calling for the overthrow of Russia’s government – and, six months later, he made this happen. The world changed.

Lenin, who had been living outside of Russia for more than a decade, was known as a theorist on the fringe of Russian political society, shaping Marxist thought to support his own theory of change. Karl Marx had envisioned a number of ways for a society to move to a system in which workers controlled the means of production. But Lenin saw only one way: through the violent overthrow of the existing government, organised by a dedicated group of professional revolutionaries. Lenin brought this scheme with him to Petrograd (now St Petersburg). There, his party took charge of the worker’s organisation that had been sharing power with a provisional government since the abdication of the tsar. But it would be more than five years before Lenin’s party secured absolute power in Russia. Millions died along the way.

Lenin’s theory of change was a theory of social disruption, of imposing a shift so radical that a society could not go back to the way it had been. Such disruptions don’t just happen randomly. There is a set of conditions required to launch them, and there are particular circumstances in which the initiators of the disruption tend to succeed in their aims.

The core characteristics of the kind of disruption I’m describing, as we’ll see in the historical episodes that follow, are that it: 1) stems from a loss of faith in a society’s central institutions; 2) establishes a set of ideas from what was once the fringe of the intellectual world, placing them at the centre of a revamped political order; and 3) involves a coherent leadership group committed to the change. These disruptions are apparent in, but not synonymous with, some of the events commonly called revolutions. Disruptions don’t always change who is in charge – they are, in fact, sometimes necessary to preserve a government that is on the verge of failure. But they will at the very least change the way that a governing group thinks and acts.

Disruptions bring a profound shift in people’s understanding of how the world around them works. They contrast in this way with less radical societal changes, based on an existing thought system: for example, the English ‘revolutions’ of the 17th century, which changed the balance of power between king and parliament without altering the basic system of government. Ideological change is crucial for major societal change, such as that pursued by Lenin, because societies promote ideologies that support their way of doing business – and if the way of viewing the world doesn’t change, the way of doing business isn’t going to change either. It’s easy enough to look to the past to find discarded ideas that were once central, such as the theory that kings rule by ‘divine right’.

Importantly, periods of challenge that have similar causes will not always have similar ends. One could argue – as Barrington Moore Jr did in his 1966 study of the social origins of dictatorship and democracy – that a change of political system will occur in a society where there is a serious disjuncture between coexisting modes of economic activity, such as traditional agriculture and capitalist enterprise. Or one could argue that a split between those who drive economic activity and those who hold political power is a precondition for change. But there is a lot of room for leaders to make choices in such circumstances that will shape very different outcomes. The first of these scenarios could quite reasonably be taken as describing both the United States and Russia at the turn of the 20th century, but there was no US equivalent of Lenin’s seizure of power.

The model for disruption that I’m proposing does not predict that radical change will occur because of specific structural issues such as those described by Moore, or that there is an inevitable outcome to a set of issues. What I am suggesting is that, when a political system is undermined by events such as economic failure, defeat in war or environmental catastrophe, that political system is going to have to change or fail. Success or failure depends on the choices that leaders make, and the ability to give people a fresh set of ideas that will help them see a new way forward.

The outcome of a disruption is often completely unexpected to contemporaries, and that is precisely because ideas from outside the mainstream were used to shape the solutions to the problems of the time. We can’t know in advance exactly how a disruption will end. What history can teach us is what the circumstances are that lead to a disruption. It can make us realise what we might be facing as a result of the situation we are in today.

When we look at one of the first major disruptions, one that is still influencing the world in which we live – the Roman emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in the 4th century CE – we have a case where change had been in the air for a while. In the half-century before Constantine staged the coup that set him on the path to unifying the Roman Empire under his own control, the empire had suffered through plague, massive inflation and a series of military disasters, but the tendency of leadership had been simply to try to make old systems work better.

Constantine sent a completely different message when his regime imported concepts from a fringe movement, Christianity, to support its own legitimacy. In doing so, Constantine made use of a small number of Christian advisers, who shaped a new relationship between the Church and Roman society, and joined the closely knit group upon which he depended to run the empire.

This early example exhibits the key characteristics of a disruption: a loss of faith in central institutions (the imperial system of government), the establishment of previously fringe ideas (those of Christianity) at the centre of the political order, and a cohesive, committed leadership group that initiated the change. In elevating Christianity’s role in the empire, Constantine altered patterns of thought, replacing old ideas about imperial authority with a fresh, obviously different model of authority that told people they were moving in a new direction.

We can observe these characteristics, too, in a disruption that unfolded in the 7th century CE, when a centuries-old Middle Eastern political order collapsed. After the old system had fallen apart, the Umayyad caliph ‘Abd al-Malik adapted the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad to provide the ideology for a new government – one that would ultimately stretch from North Africa to central Asia. Muhammad, who had died decades earlier, had been interested in using his visions to shape a community of believers. His revelation did not suggest that the longstanding system based on the Roman and Persian empires was soon to be overturned. But inept leadership had undermined the legitimacy of both governments through years of disastrous warfare, and tightly knit groups of Muhammad’s followers managed the rapid defeat of these failed states. When it looked like their movement would implode, ‘Abd al-Malik recognised the need to rebuild the centre of Islamic society, introducing new rules for the community so it could move forward.

One thing that helped both Constantine and ‘Abd al-Malik in spreading previously marginal ideas was that they could effectively control the available media for mass communication – such as coinage bearing their message and the pronouncements that would have to be read out at public festivals. Another way to get the message across was through impressive building projects, such as the Dome of the Rock shrine in Jerusalem, built by ‘Abd al-Malik. These monuments enabled people to visualise the new order as something stable.

The deft use of media was crucial in the next great disruption to shape European history: the Protestant Reformation of the early 16th century. Around 70 years before Martin Luther posted his 95 theses challenging the notion of purgatory – the place where souls had to wait before going to heaven – and the validity of the indulgences one could purchase to hasten the path forward, Johannes Gutenberg had invented the printing press. Luther proved to be a master of the new medium, recognising that successful communication needed to be short, to the point and in his audience’s own language. The Catholic Church still issued its pronouncements in Latin. Luther told people they could receive God’s word in German.

Luther was a brilliant polemicist with a powerful message, but he was not alone. He wouldn’t have survived without the support of Frederick of Saxony, his patron before the decisive moment in 1517 when he posted his challenge to Catholic doctrine. Frederick remained his protector even after the dramatic moment in 1521 when Luther defied the Holy Roman emperor Charles V, standing up before the emperor and his court and refusing to retract his writings.

Charles was ill prepared. He grew up in the Netherlands, was a teenager when he took the throne, and knew little of Germany. There were concerns about his capacity among the leaders of German society, and concerns about the way the Catholic Church’s sale of indulgences was draining money from Germany at the very time more cash was needed to fund prospective wars with the advancing Ottoman Turks. The Catholic Church was damaged by widespread accounts of papal corruption.

Frederick represented German political leaders who had lost faith in the political direction of the Holy Roman Empire. Luther’s alternative ideology gave their movement a substance that previous efforts at reining in the power of emperors and popes had lacked. In the decades after Luther’s defiance of Charles, the princes of Germany formed a political league, drawing from Charles the concession that ‘Protestant’ states could be legitimate states, and inspiring further Protestant movements in England and the Netherlands.

Ultimately, the Protestant disruption would end Catholic dominance of intellectual life, open the door to new forms of scientific enquiry, and enable the development of European nation states. One further result was to allow new thinking based on classical political theory instead of the Bible.

More than a century later, the English philosopher John Locke mounted his own momentous challenge to religious ideas – and the events that followed further illustrate the chief characteristics of disruption. Locke opened his Two Treatises on Government (1689) by demolishing an argument that the divine right of kings was based upon the political structure, authorised by God, of the Garden of Eden. In the second treatise, he announced his view that the main reason that people agreed to put themselves under a government was the preservation of their property, which could happen only if there was ‘common consent’ as to the standard of right and wrong. Tyranny, he wrote, is ‘the exercise of power beyond right’.

Locke argued that a person who exercised power in a way the community did not authorise did not have the right to be obeyed. Eventually, this idea helped to justify the rebellion of England’s 13 North American colonies against the king, George III. An extreme version of Locke’s thought was popularised by Thomas Paine in his widely read pamphlet Common Sense (1776), in which he made the case that the English monarchy was illegitimate – that it had been imposed on an unwilling population.

George III had the better army, but military might was insufficient to quell a rebellion based on Locke and his followers’ powerful ideas about what a just society should look like. Just as important for the Americans’ ultimate success was the development of a group of people around George Washington, including his allies Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, who knew how to work together to turn the abstract ideas of political theorists into viable institutions.

The Americans who opposed George III were opposed to the idea that a powerful central government could order them around. However, they soon realised that the weak Articles of Confederation that had united them in the war were insufficient to hold them together for the future. The fact that a constitutional convention could be summoned to create a new government is a sign that one of the crucial aspects of a successful disruption is that it creates space in which people can discuss new ideas. It was precisely the failure to maintain such a centre that would destroy the effort to form a new government in France following its own uprising.

Lenin was an avid reader of histories of the events in France between 1789 and the emergence of Napoleon Bonaparte as France’s ruler 10 years later. There were meaningful parallels. Just as the Russian tsar Nicholas II undermined his regime with his conduct of a war with Germany, so the French king Louis XVI persistently undermined his own government and allies in the years after he summoned the Estates General, a governmental assembly, in 1789. The king hoped to solve a financial crisis stemming from France’s vigorous support for the American rebellion against Britain. But people had already lost faith in a court they regarded as inept and corrupt. France had not developed elective institutions prior to that point, so the French court lacked a clear idea of how to manage the Estates General when it came together.

Louis XVI was soon a virtual prisoner in his own palace, while groups antithetical to his interests established an alternative military structure and a national guard, and began writing a new constitution. Even then, Louis could have survived if he had allowed that becoming a constitutional rather than absolute monarch was a reasonable option. But he didn’t. He conspired with other monarchs to overthrow the reform movement in France, thereby undermining centrists who would have allowed him to retain his throne. In so doing, he opened the door to Maximilien Robespierre and other radicals with bold ideas, who claimed that moderation was undermining the revolution – that it could succeed only if traitors were removed and a new state, founded upon the promotion of virtue, replaced the dysfunctional civic constitutions favoured by moderates.

Robespierre, who achieved dominance in French politics as chair of a committee to oversee France’s war effort, defended and enhanced his power by pressing French politics to the extreme. He established a quasi-judicial process whereby political opponents (including former allies) could be speedily executed. Depending on terror to support his vision of a new society, Robespierre wrecked the emergent democratic institutions that had been shaped in repeated efforts to draw up a new French constitution. After Robespierre himself was executed, the force of the revolution dissipated until Napoleon took over.

The French example stands as a disruption that succeeded in destroying previous institutions without succeeding in building a lasting alternative. It underscores the importance of having political leadership with a clear vision at the moment an existing system of government is overthrown. This was the sort of leadership Frederick of Saxony provided, as had Constantine and ‘Abd al-Malik. And the great strength of the framers of the Constitution of the United States was their understanding that radical change could be achieved through compromise. As Robespierre showed, resorting to violence to impose new standards on a population was a recipe for disaster.

How does Lenin fit into this picture? When he returned to Russia, the central institutions of the tsarist regime had collapsed and the existing provisional government had no electoral mandate. Lenin dominated the small revolutionary group taking over the worker’s movement that shared power with the government. Without Lenin’s ability to organise a cadre of subordinates, the revolution that he hoped for would not have come to pass in October 1917.

Lenin maintained power through a brutal civil war. He created a secret police apparatus that murdered thousands, as millions more died through starvation, battle and disease. Eventually, however, he realised that the policies he had used in wartime would not work in peacetime – reflecting an ability to adjust to circumstances that had made leaders successful during previous disruptions. Lenin’s New Economic Policy, essentially state-sponsored capitalism, gave people a vested interest in what might generously be described as a modified communist regime. Yet Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin, destroyed the New Economic Policy with his programme of forced collectivisation. His homicidal regime ensured that the Soviet Union could never offer a viable alternative to Western capitalism.

Another profoundly violent 20th-century disruption, the rise of Nazism, had roots in a theory that implied that nations must inevitably be in competition. Just as within each nation there was an ongoing contest for survival, and government should be geared towards supporting ‘winners’ over ‘losers’ in this struggle, so too there could only be ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in foreign affairs. This view, promulgated by Herbert Spencer, became known as social Darwinism, and it was supported by the pseudoscience of eugenics, developed by Spencer’s contemporary Francis Galton. Although he was English, Spencer’s theories gained greater currency in the US, where Galton’s eugenic theories were taken up to support restrictive immigration policies and the state-sponsored sterilisation of prisoners on the grounds of ‘mental deficiency’. One person who found such laws appealing was Adolf Hitler.

Hitler’s political success stemmed in large part from the fact that his assertions about Germany’s path – that it could have won the First World War, that it had been stabbed in the back, and that its problems could be solved by undoing the treaty that had ended the war – were familiar to the electorate from other sources. These positions were lies, but the lies were popular. Hitler’s extreme version of racist social Darwinism was initially on the fringe of German thought but, linked to his anticommunism, it was tolerated outside Nazi circles.

Yet an anticommunist message backed by lies would not be sufficient to explain Hitler’s rise to power. Echoing previous disruptions, this required the disintegration of faith in government. In this case, the loss of faith resulted in large part from the policies pursued by Germany’s centrist chancellor: in response to the Great Depression, he followed conventional wisdom by cutting public spending, thereby increasing the impact of the downturn and damaging the centre-Right alliance that had ensured his election. As the depression deepened, Hitler’s Nazi Party attracted ever more attention, something enhanced by Hitler’s ability to make use of new technologies, especially radio, and his vigorous style of campaigning. Still, when Germany’s president, Paul von Hindenburg, made Hitler chancellor in January 1933, Hindenburg had been convinced that Hitler could be controlled.

It would not be two full months before Hitler created the legal conditions for his dictatorship. The Nazi Party was still not yet recognised for the murderous institution it was when, in 1936, the world gathered in Berlin to celebrate the Olympic Games. Hitler sounded enough like other conservatives – the parallel between Jim Crow laws in the US and Germany’s antisemitic legislation was adduced in support of the appearance of the US at the games – and he had strong anticommunist credentials. These factors, along with dread of another war, made European governments unwilling to stand up to Hitler until war became inevitable.

The disruption led by Hitler relied on a collapse of faith in institutions, on the appeal of Hitler’s novel version of German nationalism to a society reeling from economic collapse and violence, and on the high level of discipline in the Nazi movement, within which Hitler had built a core leadership group. And his rise was aided by the blindness of the political establishment.

What can disruptions of the past – with their diverse outcomes – tell us today? The value of history is that it enables us to detect patterns of behaviour in the present that have had serious consequences in the past.

Today, there are signs that the US and European liberal democratic systems are under threat. The most obvious of these is a loss of trust in public institutions. Factors such as the willingness of Western governments to allow widespread impoverishment, the weakening of labour organisations, and the failure to provide adequate healthcare and other necessities, feed into powerful movements seeking to undercut the mainstream political system.

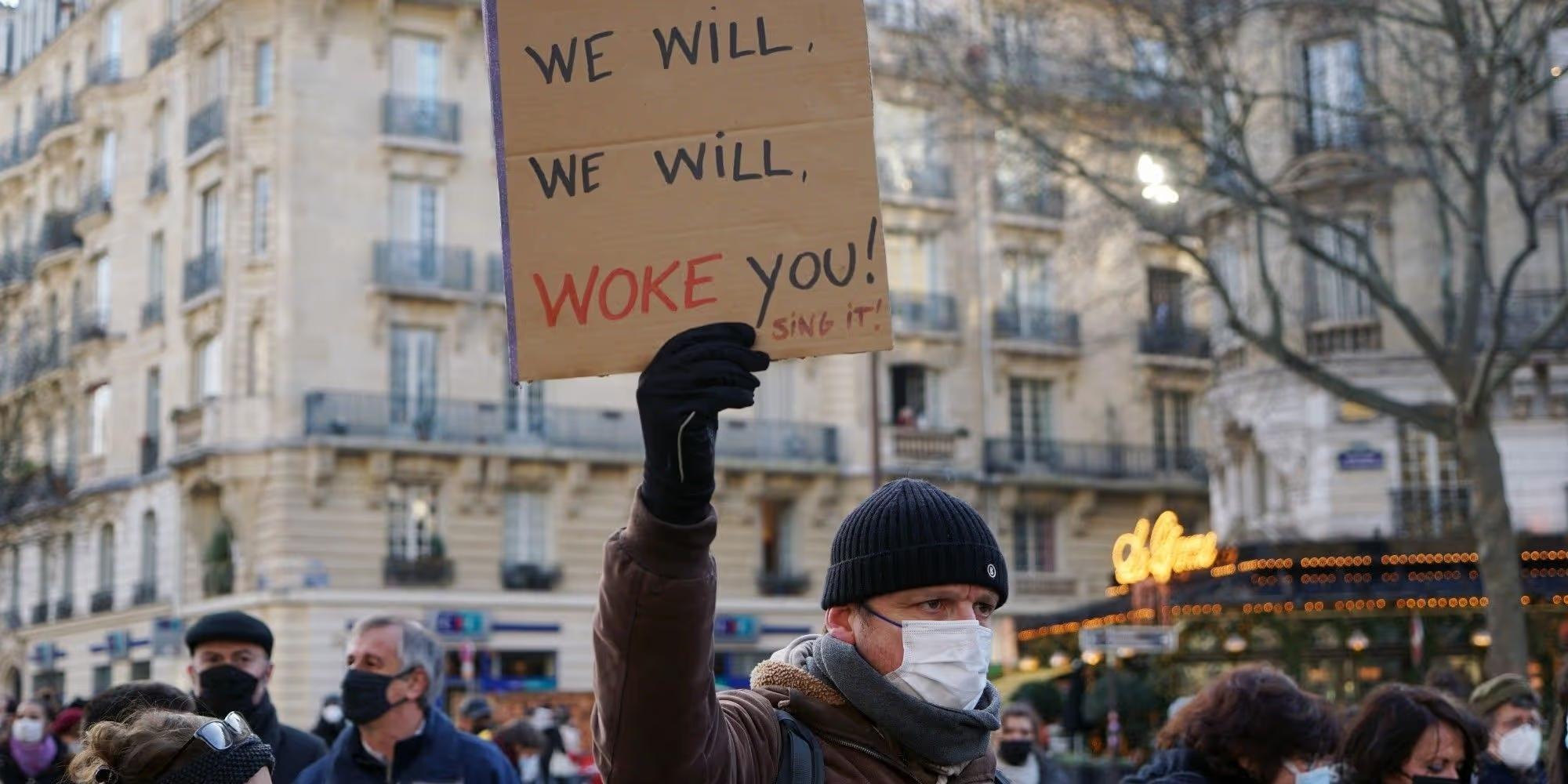

So too we see ideas from the intellectual fringe informing these increasingly powerful political movements. Some of these movements use social Darwinist ideas to claim, for instance, that public welfare is undercut by immigration. In Europe, the normalisation of nationalist groups such as the one supporting Éric Zemmour’s bid for the French presidency, or Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz Party in Hungary, is threatening established political norms. In the United Kingdom, some advocates of Brexit have translated traditional English exceptionalism into a form of hypernationalism in terms that, like those of the former US president Donald Trump’s supporters, echo social Darwinist doctrines. The prevalence of belief in lies, such as the lie that Trump won the 2020 election, is evocative of the universe of false assumptions that spread in Germany during Hitler’s rise to power. To combat the fissures that election lies, immigration fantasies or antivaccination movements represent, Western governments should recognise that the prevalence of fringe thinking is a sign that they are failing.

The path to restoring faith – which could lead through the sort of disruption that has preserved societies in the past – will offer real help to those who have been left behind. The underlying principle of liberal democracy is the contract between government and the governed. Government has a responsibility to reign in corporate power that undermines public welfare and spreads falsehood, just as it has a responsibility to ensure that people have access to the goods and services they need. This will require practices very different from ‘politics as normal’. It is a critical lesson from history that, when normality fails, change will come.

The signs are that we’re in a time that is ripe for disruption. But what sort will it be?

David Potter